Updated August 6, 2012

If I were to claim one single main achievement for Framework, it would be this: the journal was among the quickest to recognize the need, and to argue, for the elaboration of a transnational critical-theoretical discourse, which would leave no 'existing' frame of reference undisturbed. [Paul Willemen]

In a 1994 dialogue with Noel King, Paul Willemen noted that in the varied body of critical writings associated with cinephilia there exists a recurring preoccupation with an element of the cinematic experience 'which resists, which escapes existing networks of critical discourse and theoretical frameworks' ([Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory] 1994: 231). Willemen and King locate this resistant element specifically in the cinephile's characteristic 'fetishising of a particular moment, the isolating of a crystallisingly expressive detail' in the film image (1994: 227). That is, what persists in these cinephilic discourses is a preoccupation or fascination with what the various writers 'perceive to be the privileged, pleasure-giving, fascinating moment of a relationship to what's happening on screen' in the form of 'the capturing of fleeting, evanescent moments' (1994: 232). Whether it is the gesture of a hand, the odd rhythm of a horse's gait, or the sudden change of expression on a face, these moments are experienced by the viewer who encounters them as nothing less than a revelation. [Christian Keathley, 'The Cinephiliac Moment', Framework, 42, 200]

The concept of 'double outsideness' in the work of a displaced film-maker is articulated in essays on Sirk and Ophuls, while the essay 'An Avant-Garde for the 90s' usefully connects Willemen's early work in film studies to his later preoccupation with non-Euro-American cinema.

Overall his work challenges dominant preconceptions about cinema and its attendant critical discourses, and makes itself available for broader application. Looks and Frictions is by no means an easy or comfortable read, but in its reminder to the critic to consider their own position in relation to the objects of criticism, and of the need to ground criticism in the real, to fit social and historical circumstances and determinants into even the most esoteric flights of theoretical fancy, it is both productive and provocative and deserves to be widely read. [Ben Goldsmith, 'To Be Outside and In-Between: On Paul Willemen, Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory', Film-Philosophy, 2.1, 1998]

Film Studies For Free was saddened by the crushing news of the death, just over a week ago, of Paul Willemen, the brilliant and hugely influential film theorist, critic, programmer, historian and, above all,

activist.

Willemen started work at the British Film Institute in the early 1970s, and was part of the editorial group of Screen in the second part of that decade. In 1976, he became involved with the journal Framework, which had been founded two years earlier by Donald Ranvaud, Sheila Whitaker, and others at Warwick University. He took over as its editor in 1982

, handing over that role fully to Jim Pines between 1986 and 1989.Working as a BFI employee with film museums and cinemateques, he collaborated over many years with the Edinburgh Film Festival. In 1986

, in that festival's 40th anniversary year, he, Pines and June Givanni organised a famous "Third Cinema" conference.

Questions of Third Cinema, the

landmark volume that resulted from the conference, co-edited by Pines and Willemen, was in part a transcription of contributions that importantly explored the "cinema of diasporic subjects living and working in the metropolitan centres of London, Paris, New York" (p. vii) as well as elsewhere.

As well as one of Framework's principal contributors over the years, he was also author and editor of many other important books, pamphlets, and articles on cinema. Some of these are pictured or named above, and more are listed, passim, below. Having dropped out of his Belgian university in 1960 ('

And I never went back'), Willemen's first proper experience of working in a higher educational context was a

three month trip in 1980 to Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia, where he participated in many groundbreaking seminars on cinema and film theory.

In the late 1990s, he was Professor of Critical Studies at Napier University in Edinburgh, and from 1999 until his retirement in 2008 he was Research Professor of Media Studies at the University of Ulster. In memory of Paul Willemen and his contributions to Film Studies,

Film Studies For Free is very honoured to present, below, some wonderful, fitting tributes to him and his work by four people who knew and worked with him over the years: Adrian Martin, Lesley Stern, Martin McLoone and Michael Chanan. Thanks very much to each of them for their words.

Below their tributes are

FSFF's customary links to online publications of Willemen's writing and to discussions of his work.

It is appropriate on such occasions to wish that the person who has just died will

rest in peace. After his struggles with illness in recent times, especially,

FSFF certainly wishes that for Paul Willemen. But to honour his inspirational contribution to our field properly, those of us who work in his wake -- on cinephilia, on comparative film studies, on film and politics -- need more than ever to take up his passionate restlessness, even as it would impossible, or undesirable, to embrace every one of his personal stances or attitudes. He will always be in our memory. We will forever be in his debt.

Indelible Memories of Paul Willemen

Paul Willemen is sometimes off-handedly regarded, by those who haven’t looked at his work terribly closely, as someone who was (and remained) part of a horde of ‘Screen theorists’ emerging in the 1970s, single-mindedly dedicated to enforcing the shotgun marriage of Lacan, Althusser, Barthes and Derrida within the then institutionally burgeoning field of cinema studies in the UK. In fact, Paul always followed a very singular path, and he was fiercely critical of many of the developments and tendencies around him.

His distinctive contribution begins, in my opinion, with the early meditation (published in 1974) on the concept of inner speech in cinema, via the theories of Boris Eikhenbaum. It was a concept he was to return to again and again, in key articles of 1981 (“Cinematic Discourse – The Problem of Inner Speech”) and 1995 (“Regimes of Subjectivity and Looking” [The UTS Review 1(2)). What was inner speech all about? Fundamentally, a doubling: images arise (in the mind, and on screen) with words attached, encoded in their veritable DNA; no image exists in some pure realm of visual expressivity or imagination, but rather is always-already enmeshed in what Paul would refer to ‘webs of meaning’, threads of social discourse.

Beyond being a specific trope, I believe inner speech served as a sort of figure or metaphor for Paul, and for his way of thinking. Nothing (certainly no film text) was ever pristine for him, everything was produced in an intersection of forces, lines, influences and contexts; each person, each action, each object was the result of a ‘subject formation’ that needed to be grasped and explicated. But, as determining as such a subject-grid could be, it also – as in the always unstable interplay of images and inner speech – provided a space for interference, short-circuiting, and thus for internal modulation and change.

Paul had little faith in the movement known as cultural studies as it emerged in the 1980s, and even less in its almost religious invocation of ‘popular resistance’; but he did believe in the hopeful force of desire (starting with the desire for cinema itself, cinephilia), and in its constant process of mobilisation – a mobilisation that had to occur not just in writing and teaching about film, but also in editing and publishing (his years at the helm of Framework, and with various BFI book and DVD projects), in the programming and presenting of work (the film culture of organisations and festivals), and in active, collaborative relations with real filmmakers (and Paul knew many, from Stephen Dwoskin to Amos Gitai).

Over the last 15 years of his life, Paul sketched out, in various places, an ambitious program for a ‘comparative film studies’ of world cinema; these pieces need to be collected in a book now, because they constitute a theory – and a critical-pedagogical practice – that we sorely need. Paul was someone who (as the saying goes) didn’t suffer fools lightly, and he made a polemical show of denigrating most forms of sloppy, sentimental humanism; but his politics was of a truly passionate kind, and its core was summed up in the title of a film that he championed: So That You Can Live.

Adrian Martin

Associate Professor, Arts

Monash University (also see: Adrian Martin, 'The Front', Filmkrant, August 2012)

Beguiled. I was beguiled by Willemen. The first film we ever discussed (or argued about) was Don Seigel’s The Beguiled, a baroque Freudian parable in which Clint Eastwood plays a Confederate soldier who has his leg cut off by a group of demented Southern women. It was 1975 and I had just scored a job as assistant publicity officer in the Regional Film Theatres Dept at the BFI. Soon after I arrived Paul Willemen came in as boss of the section. I knew who he was, had earnestly devoured the Edinburgh Film festival publications, and gobbled up all the film theory emerging at that time. I was enthralled by the distant figures who populated the stage: Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey, Sam Rohdie, Stephen Heath, Claire Johnston and Paul Willemen among others. Willemen was the most mysterious and attractive to me: striding or lounging or soapboxing, in his leather jacket and boots he seemed to me a sort of European intellectual Marlon Brandon.

At the BFI he ignored me. I mainly did filing, boring boring, but occasionally was allowed to write capsule reviews. Then one day, doing his job, he read my few words on The Beguiled and instigated an interrogation. It was terrifying. It was just a measly little paragraph but I had to defend it as though it really mattered, as though every word mattered. I had never been challenged about film like this. But it was also exhilarating. And I learnt a few things about Paul: for him the intellectual stakes were always high, no matter what the context, no matter who the interlocutor; he had a cinephiliac taste for the baroque and trashy; he had a droll sardonic sense of humour which was integral to his critical modus; for all his association with high theory he was also a pragmatist, clear-sighted about what working in cultural institutions was about.

Within a few months I had moved to Australia, but over the years and across continents—meeting at conferences and festivals and bookshops—Paul and I became friends. We also fell pretty much out of contact in the last fifteen years or so. When I heard that he had died, an unexpected and terrible grief roared into the world. And a sense of loss. Of something lost from the world. Not just the person called Paul Willemen, but what he stood for. For many people. For someone with a not undeserved reputation for being cantankerous, aggressive, acrimonious, polemical, scornful, contemptuous he had a huge network of friends across the world. How come? And what would they all say? Very different things I imagine (many of his friends would probably not be inclined to talk to one another) so it is disingenuous to try and conjure into being a sense of PW through a few personal memories and encounters. But that is what I have, and how I can do it, and I hope that this question (of his irascibility combined with sociality) though submerged in what follows, will rise to the surface.

Two scenarios, two extended exchanges: one taking place in the context of Framework, the other in BFI publishing.

In the first half of the 1980s I was working on experimental Japanese cinema and spending time in Japan (living in Australia), and Paul was editing Framework. He cajoled me into writing up some of my material for the journal. This was at a time when I had left the academy and was very disenchanted with academic writing in general, screenese in particular; I also found the experience of being in Japan, of researching the various strands of experimentation from the sixties through to the contemporary scene, hyper stimulating but also culturally very difficult. I did not know how to write about it, how to find a language that was true to the history, that was informative for people who had no familiarity with these films and their cultural location, but that nevertheless somehow eschewed the anaemia of a disaffected third person voice.

To some extent I saw Paul as the enemy here (a representative of screenese). But Paul liked to have enemies, and I liked the Framework project. Paul’s own account of the emergence and early history of the journal is on the Framework web site, but let me just say how significant the Framework intervention was and remains today, indeed how it is differentiated from much of today’s euphoric babble about the global, about world cinema. Although Framework was coherently dedicated to giving voice to, to researching, and unearthing voices, films, figures from outside the contemporary Euro-American mainstream it was remarkably eclectic and heterodox. Not only in the range of materials (interviews, archival documents, industry figures, theory, criticism, history, bibliographies, filmographies) but in modes of writing, modes of address.

Throughout the years Paul was tenaciously committed to theorizing national cinemas and the concept of the national (instantiated in Theorizing National Cinema, the book he edited with Valentina Vitali) but he was also militantly opposed to institutionalized theory, to a professionalization of film studies which was totally ungrounded, lacking in historical research, untethered from political perspective and meaningful critical engagement. He practiced this precept in his own engagement in a variety of forums—film festival events and publications, involvement in various alternative cinema campaigns, writing encyclopaedias (on horror films for instance, and a monumental work on Indian cinema), collaborating on writing monographs and editing collections, and publishing. He was always curious about location, audience, address, and about how to write differently for different contexts and in order to make different kinds of interventions.

So Paul patiently listened to me going on about Japan and the impossibility of writing about it. Interjected questions. Never patronized, never accused me of self-indulgence and preciousness. Simply assumed I would get it done. So I did. As editor he was dealing with lots of writers, not to mention filmmakers and others. From different places, different cultural formations. Making new friends, keeping up old feuds. And with all these balls in the air he had this fabulous capacity to give attention, to focus energy, to shape discursive threads and formulate a critique out of discontinuous and fragmented social entities.

Some time after that, though the timeline is hazy for me now, Paul solicited and eventually rescued my Scorsese project from oblivion. He was a great editor, never dodging an argument, never imposing a point of view (even though we argued), but also never reluctant to cut my wordiness. I derived much pleasure from trying on occasion to outfox him by writing some sections that I knew he wouldn’t much like in such a way that he would find it impossible to cut. Sometimes it worked.

I will be eternally grateful to Paul, first of all for suggesting Scorsese as a topic (for seeing something that I myself could not see), and secondly for publishing The Scorsese Connection. I cannot imagine where else I could have taken the project at that time. It did not adhere to any of the familiar protocols of academic publishing in Britain or the U.S. But his gesture is symptomatic more generally of his work as both a publisher and cultural activist, often forging pathways and opening up viewing and reading parameters, inflecting the conception of cultural production through frictional in-between spaces.

Paul’s own book Looks and Frictions was part of the same “Perspectives” series. In her introduction Meaghan Morris suggests thinking of Willemen as “a thoroughly pragmatic utopian.” One aspect of that utopian pragmatism (to invert the terms) is manifested in the number of collaborators Willemen has had; the way his name is linked with other names on major books and projects for instance (Claire Johnston, Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Jim Pines, Valentina Vitali to name a few) suggests a pragmatic approach to cultural production as joint work, involving provisional alliances, and assumed intellectual and political negotiations. The utopian dimension was socialist, not always in easily recognizable terms, but always concerned with intervention and underpinned by the belief that all transformative aspirations need to be two-way, to arise out of knowledge and analysis.

And then it came about that I fell out of contact with PW so I cannot speak of recent years. Eventually we had a very long and fierce and exhausting argument, as I remember it about affect and performance and cinephilia (his exchange with Noel King about cinephilia in Looks and Frictions, incidentally, is a pleasurable read and a truly collaborative intellectual working-through). In martialling his ammunition Paul showed me Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (Cloud-CappedStar), which was a revelation. But we were each intransigent. We parted with affection on that occasion but somehow our exchange had run its course, and we never really connected again. Hearing of his death I felt overwhelming regret at losing touch. But then I remembered that Paul was the least sentimental of beings. I remembered being beguiled. I remembered many things about PW and his work that I do not want to forget. His dire dystopic warnings—just as much as the utopian pragmatism—seem pertinent today. It is timely to be reminded that the intellectual stakes should be high.

Lesley Stern

Professor, Visual Arts Department,

University of California at San Diego

Paul Willemen embraced academic life relatively late, arriving at the University of Ulster at Coleraine in 1999 after a short spell at Napier in Edinburgh. His reputation and standing within academic film studies was, of course, formidable by this stage. He had played a key role in the 1970s and 1980s in defining the subject area in the UK and helping to shape and mould both the subject’s theoretical terrain and its institutional structures. These earlier years were characterised by his dual commitment to promoting a ‘cinephiliac’ understanding of popular cinema – especially mainstream American cinema – and to promoting an understanding of alternative cinema in all its formal and political diversity.

In his years at Ulster, he pursued two further theoretical obsessions – the concept of comparative film studies and the pleasures of and political contexts of the action film, especially in its heroic classical mode. He entertained a rapt audience at Ulster during his professorial lecture by showing some muscle-bound examples of the genre and offering a political and economic critique of the Italian peplum tradition. He was also vexed and intrigued by the concept of national cinema and his dissatisfaction with the ‘national’ was the spur to his interest in comparative film studies. Ulster provided him with an incongruous but strangely apt environment to pursue this interest.

He was also very generous with his time. When my own study of Irish cinema was published in 2000, he attended a launch event in Dublin on the Monday evening and deposited a three-page critique of the book in my pigeonhole at Coleraine on the Friday morning. He pointed out the theoretical shortcomings of the book and spotted an ambiguity at its centre as well as offering a reasoned and wholly professional critique. He was, of course, spot on as usual and it was the measure of his erudition and insight that I was neither annoyed nor dismayed by his critique. He was right. And since I knew well that Paul did not suffer fools, as he saw them, gladly I was also flattered by the attention. This is what made him, despite his formidable intelligence and learning, popular with students as well. He took the time to take them seriously.

Paul was not an institutional person and he always found the workings of bureaucracy draining and straining and in the end, I think he found the University system counter-intuitive to his conception of learning and thinking. He was, however, a good colleague and friend and when he retired in 2008 I certainly missed having his intellectual engagement around the place. I assumed that he would continue to write and teach in retirement, operating with the relative freedom of the independent scholar. It is extremely sad that his illness and early death has deprived us of one of the most accomplished and challenging intellects in our field.

Martin McLoone

Prof. of Media Studies,

University of Ulster

Sad to hear of the death of Paul Willemen. I didn't know him well; our relationship was that of professional colleagues. And I often disagreed with him. But he was a splendid intellectual interlocutor. I recall in particular a summer afternoon in Italy in the early 1980s where we coincided at the Pesaro film festival. Pesaro had come into its own in the late 60s as perhaps the most radical of Europe's film festivals, and among other things, a place to see new films from Latin America, of which there were several that year. Simply meeting there was a sign of certain shared values about film and politics. We wandered off between two screenings to eat ice cream and got stuck into an argument that I've never forgotten, about artistic languages, in which he fiercely defended a Lacanian position that I couldn't accept because I didn't think it worked for music. I came to the conclusion that Paul didn't have a musical ear, but also that I needed to try and grapple with Lacan (something I only did many years later).

I have another indelible memory of Paul from the end of the 90s. I had run into problems at the college where I was then teaching. In those early years of New Labour, a new non-academic Dean had been appointed on the promise of bringing contacts with industry. She quickly proved a disaster who thought that academic committees were like the rubber-stamping variety she'd known at the BBC, whence she came. For various reasons too complicated to rake over, I was the poor sod who got scapegoated with a specious disciplinary charge that the institution was subsequently forced to withdraw on legal advice. But not before a large number of friends and colleagues had written emails to the Head of College in my support. The very first to write, in an exemplary demonstration of solidarity, was Paul, who, in a few elegant but trenchant lines, charged the college with infringement of academic freedom. His was a principled voice of a kind that we urgently need more of today, and I'm glad at least of the opportunity to pay tribute to him here.

Michael Chanan

Professor of Film

Department of Media, Culture and Language

University of Roehampton, London

Putney Debater website

- Paul Willemen, 'An Introduction to Framework', Framework, 42, 1999

- Paul Willemen, 'On Framework', Framework, (date unknown)

- Paul Willemen (interviewed by Deane Williams), 'The Double Access, Film Culture and the Ossification of Film Studies', Screening the Past, 23, 2008 (scroll down)

- Paul Willemen, 'Note on Dancer in the Dark', Framework, 42, 1999 (scroll down)

- Paul Willemen, '[Obituary] Eduardo Guedes [of Cinema Action]: His creative energy widened recognition of the independent film-maker's art', The Guardian, October 17, 2000

Other online discussions of Willemen's work and influence:- Acquarello, 'Questions of Third Cinema edited by Jim Pines and Paul Willemen', Strictly Film School, March 12, 2008

- Homi Bhabha, 'The Commitment to Theory', new formations 5, Summer 1988

- Jean-Loup Bourget, 'Sirk and the Critics', Bright Lights Film Journal, 48, 2005 (originally published in Issue 6, 1977)

- Jeremy B. Butler, 'Imitation of Life (John Stahl, 1934. Douglas Sirk, 1959): Style and the domestic melodrama', from Jump Cut, no. 32, April 1987, pp. 25-28

- Michael Chanan, 'The Changing Geography of Third Cinema', Screen Special Latin American Issue (edited by Catherine Grant and Jackie Stacey), Volume 38 number 4 Winter 1997

- Ben Goldsmith, 'To Be Outside and In-Between: On Paul Willemen, Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory', Film-Philosophy, 2.1, 1998]

- Lynne Joyrich, 'Written on the Screen: Mediation and Immersion in Far from Heaven', originally published in Camera Obscura, 54, Volume 18, Number, 2003

- Christian Keathley, 'The Cinephiliac Moment', Framework, Issue 42, 2000

- Amy Lawrence, 'The Face of a Saint', The Passion of Montgomery Clift (University of California Press, 2010)

- André de Alencar Lyon, 'The Afterlife of Melodrama: Roger Michell's Changing Lanes', SURJ., Spring 2004

- New Adrian Martin, 'The Front', Filmkrant, August 2012

- Tom O'Regan (interviewed by Deane Williams), ‘The Circulation of Ideas’, Screening the Past, 26, 2009

- Ryan Powell, 'Putting on the Red Dress: Performative Camp in Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows,' Forum, Issue 4, Spring 2007

- Niall Richardson, 'Poison in the Sirkian System: The Political Agenda of Todd Haynes's Far From Heaven', Scope, Issue 6, October 2006

- Peter Stanfield, 'Notes Toward a History of the Edinburgh International Film Festival, 1969–77', Film International, Issue 34, 2008

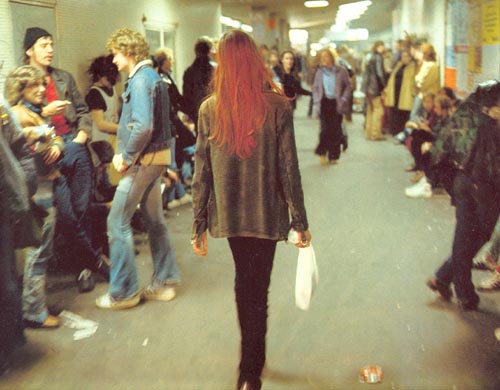

- Lesley Stern (interviewed by Deane Williams), ‘I’m going to be met by a phalanx of safari-suited men’, Screening the Past, 28, 2010